There was a man

named Benedict,

blessed by name and in fact.

Still a youth

mature in mind and heart,

God filled him with blessings and called him

as he did Abraham

to give him a descendance as numerous as the stars in the sky

and like the sand on the seashore.

Sons and daughters

following his Rule everywhere brought

the civilization of the Gospels so that

in everyone and everything God may be glorified.

Of this lineage

of this man

whose name is Benedict,

I, too, am born.

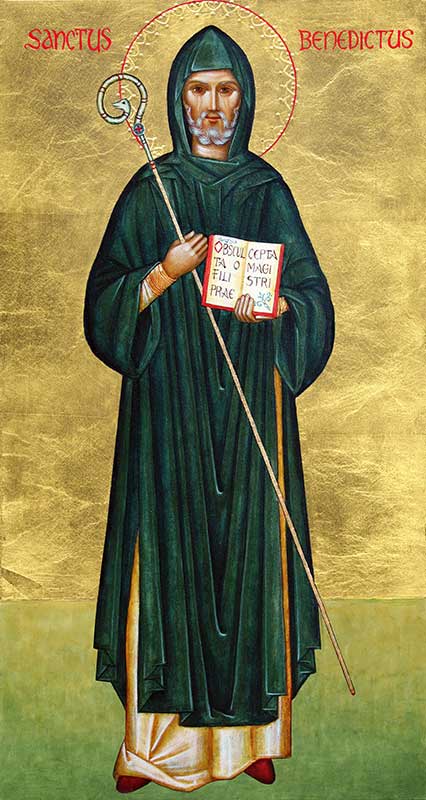

«There was a man of venerable life, Benedict by name and grace»

ST. GREGORY THE GREAT, The Dialogues, Prologue

These few lines with which St. Gregory the Great opens the Book of Dialogues, which contains the biography of the Holy Abbot, Gregory clearly outlines his most relevant aspects: a man who lived what his name expressed, who from his youth possessed a mature heart, ready to respond with dedication to the plan that God already had for him from the womb.

This maturity, the ability to discern good from evil concretized in the life of Saint Benedict a clear and decisive rejection of temporary and transitory things:

“He gave himself no disport or pleasure” says St. Gregory, instead directing his whole life decisively and resolutely towards the world that does not pass away, towards the realities that remain, which are eternal, towards Christ himself.

With Saint Benedict – a man of God with a serene face, of a venerable life, with angelic habits – we find ourselves before a figure who is both strong and meek, austere and amiable who radiates light and warmth around him.

The Rule of St. Benedict

… Therefore whosoever you are who hastens to the heavenly country,

first accomplish, by the help of Christ,

this little Rule written for beginners:

and then at length you shall come,

under the guidance of God,

to those loftier heights

of doctrine and of virtue.

(RB 73)

The Benedictine Rule: a proposal for a path of peace

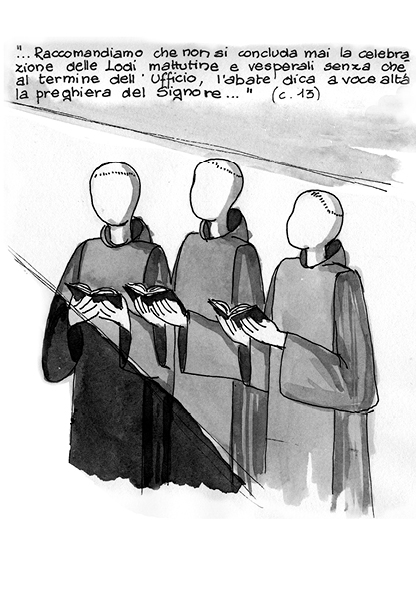

The Rule is made up of 73 chapters preceded by a Prologue which, in addition to introducing it, already contains many of the most meaningful elements that Saint Benedict wished to emphasize.

The style is calm as in a familiar discourse: St. Benedict’s aim, in fact, is not only to instruct the monks, but, above all, to make them feel like the beloved children of a “good father” who wants to help them “return to Him, from Whom thou didst depart by the sloth of disobedience.”

From the very first lines, however, it is evident that this return involves a struggle, taking up the “strong and glorious weapons of obedience” and is a journey that is undertaken “under the guidance of the Gospel”, “equipped, therefore, with a robust faith proven by the accomplishment of good works”, renouncing one’s own will, in order to put oneself at the service of the Lord, concerned with “instantly doing all that can be of benefit forever.”

To this end, St. Benedict invites the monk to entrust himself completely to the Lord “with fervent prayer” without letting himself be discouraged by the harshness and fatigue of the start, but remembering that it is He who sought us first and that nothing “can be sweeter for us than this voice of the Lord who calls us and, in his great goodness, shows us the path of life.” In fact, it is natural that it “is always strait and difficult in the beginning. But in process of time and growth of faith, when the heart has once been enlarged, the way of God’s commandments is run with unspeakable sweetness of love.”

This journey is guided and supported first of all by the Abbot, who in the monastery “holds the place of Christ” and then by the brothers who are invited to practice “good zeal” (chap. 72), enduring their mutual infirmities, competing in mutual obedience, each seeking the advantage of the other, loving each other with a chaste heart, loving their Abbot as a father and putting absolutely nothing before Christ. In this way they will all be able to reach eternal life together, since no one lives for himself in the monastery, but walks carrying the others as well.